Two Irish Martyrs

Many Irish Catholics were martyred for their faith during the penal laws. Today we look at two of these martyrs and reflected on similarities between these martyrs of old and the Christian martyrs of today.

By Conn McNally

One of the gates at Kilmallock Co. Limerick. This is one of the possible locations for the martyrdom of Blessed Patrick O’Hely and Blessed Cornelius O’Rourke. (Open source).

In late August 1578 Blessed Patrick O’Hely the Bishop of Mayo and a fellow Franciscan Blessed Cornelius O’Rourke, were hung at Kilmallock Co. Limerick.[1] O’Hely was from Connaught in the west of Ireland. After he had joined the Franciscans he went first to Spain and then to Rome. While in Rome in 1576 Pope Gregory XIII consecrated O’Hely bishop of the Diocese of Mayo. Bishop O’Hely was instructed by the pope to return to Ireland to shepherd his flock. While returning to Ireland O’Hely was joined in France by another Irish Franciscan, Fr. Cornelius O’Rourke. Fr. O’Rourke was a member of the ruling clan of the Gaelic Kingdom of West Breifne in the west of Ireland. The two Irishmen set sail from Brittany and landed in Dingle Co. Kerry in the southwest of Ireland.

Munster in the south of Ireland was in a state of turmoil in the 1570s. This was the period of the Desmond Rebellions. This was one of the most important stages of the conquest of Ireland by the English Queen Elizabeth Tudor (Elizabeth I). The English were attempt to bring the Catholic Gaelic and Hiberno-Norman lords of Ireland under direct Protestant English rule. Prior to the conquest, undoubtedly one of the most powerful lords in Munster was the Hiberno-Norman Gerald FitzGerald the Earl of Desmond. The FitzGeralds were the descendants of Norman knights who had invaded the south and east of Ireland in the 12th century. The FitzGeralds had close contacts with the native Gaelic Irish over the years. By the 16th century the FitzGeralds had adopted the Irish language, laws and customs. Importantly the FitzGeralds, like the Gaelic Irish, had remained staunch Catholics. Despite the English Crown’s conversion to Protestantism, the Earl of Desmond had remained theoretically a loyal subject but was in practice an independent prince.

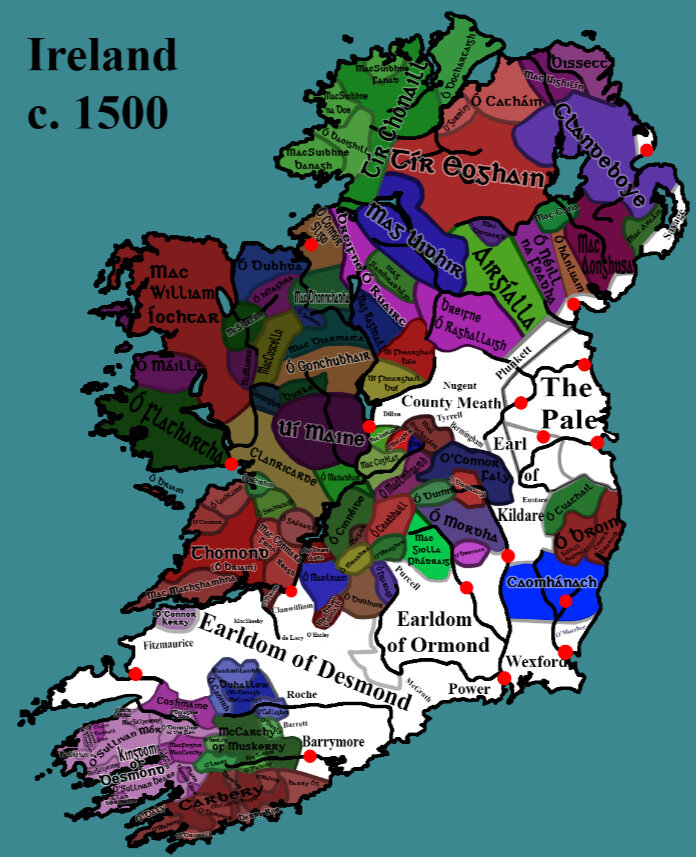

Map of Ireland in the early 16th century. The Earl of Desmond was the most powerful lord in the south of Ireland prior to the 1570s. (Open Source).

In the late 1560s the FitzGeralds of Desmond, alongside their Gaelic allies in Munster, openly rebelled against the English Crown over interference by the English Government in the FitzGeralds’ affairs and for arresting the earl. The FitzGeralds had been defeated by the Crown’s forces in the early 1570s. English troops and government officials were put throughout Munster underneath the command of the recently established English President of Munster. The power of the FitzGeralds and other local lords was much reduced. In 1579 the FitzGeralds of Desmond and their allies rebelled again. A small number of Spanish troops landed in Munster to assist the Catholic rebels. In addition, the Gaels in Co. Wicklow (south-eastern Ireland) joined the rebellion and even tried to re-establish the ancient Gaelic Kingdom of Leinster. This second rebellion seemed to have been far closer fought than the first, but the English Crown again managed to defeat the FitzGeralds in Munster. The rebellion ended with the death of Gerald FitzGerald the Earl of Desmond. The Gaels of Wicklow, led by the O’Byrne clan, managed to hold off English troops and retained their autonomy in the southeast of Ireland.

A 16th century sketch by Albrecht Dürer of Gaelic mercenaries in service on continental Europe. A large proportion of the soldiers serving in the FitzGerald army were either recruited from the Gaels of Munster or hired Gaelic mercenaries from other parts of Ireland and the western Scottish islands. (Open source).

The Desmond Rebellion had left Munster devastated. English troops often resorted to the burning of crops and the slaughtering livestock to starve their enemies into submission, causing widespread misery, desolation, and death. It was also the beginning of direct English control in much of Munster, with Protestant authorities being able to persecute the Catholics of Munster. Although in part the Desmond Rebellion was little more than an attempt by a provincial lord to resist the control of a distant queen, it was still partly motivated by the desire of Irish Catholic lords to protect their lands from colonial brutality and religious persecution.

It was under these circumstances that Bishop O’Hely landed in Munster in 1578[2], a year before the second rebellion by the FitzGeralds. O’Hely and O’Rourke aroused the suspicions of the queen’s spies in Co. Kerry. The two Franciscans were arrested and handed over to Elenore Butler the Countess of Desmond, who was the wife of Gerald FitzGerald the Earl of Desmond. The Countess treated O’Hely and O’Rourke with great kindness while they were in her captivity. She was however fearful of how the English would react if they found out the Earl of Desmond’s wife was harbouring a “popish” bishop. For this reason, she had O’Rourke and O’Hely transferred over to William Drury the President of Munster, the highest-ranking English official in Munster.

A portrait of William Drury the President of Munster. (Open source).

The Irish Franciscans were brought in front of Drury in Kilmallock Co. Limerick. Drury had only recently been appointed President of Munster and therefore persecuted Catholics with great zeal to prove his commitment and loyalty to the Crown. Drury questioned what business the two Irishmen had in Munster. O’Hely told Drurn that they were both Franciscans and the he, O’Hely, had been consecrated Bishop of Mayo by Pope Gregory XIII the Supreme Head of the Church on earth. This statement was treason in the minds of the English authorities, as Elizabeth Tudor claimed to be the supreme governor of the Irish Church. Drury informed the bishop that he was speaking like a rebel and asked if he was sure he meant to assert the pope was the head of the Irish Church. O’Hely answered that he had spoken as he intended to and was willing to suffer any torments that might result from his fidelity to the Apostolic see. Drury had the two subjected to torture to force them to swear the Oath of Supremacy that Elizabeth Tudor was the supreme governor of the Irish Church. The two Franciscans stayed true to the Faith and refused to swear this oath.

Drury, as claimed in some sources, did not have the stomach for the torture as he was in his own private conviction a Catholic. Drury order the torture to be stopped. Instead he tried a new tactic on the bishop. He sent an attendant who could speak Irish to talk to the bishop. The attendant explained in the bishop’s own mother tongue that Drury only wanted him to outwardly appear to obey the law and that he could still privately believe the pope was the head of the Irish Church. Once the bishop had made the statement that the English Crown was the head of the Irish Church, Drury would not push him further. Bishop O’Hely refused, saying that he would die a thousand deaths rather than renounce his obedience to the pope.

Fr. O’Rourke likewise stayed true to the Catholic Faith. Both men were sentenced to death. The night before he was executed Fr. O’Rourke was visited by a Jesuit priest, Fr. James Archer. Fr. Archer later wrote that Fr. O’Rourke was around 30 years old and was of a kindly disposition. The two Franciscans were hung by their habits’ girdles just outside of one of Kilmallock’s gates. Before being hung Bishop O’Hely called out to Drury to warn him he would have to answer before God for his actions. A few days after the hanging Drury was taken seriously ill. The physicians could not explain his illness. Drury admitted openly he was being punished by God for falsely executing the two martyrs.

The ruins of Askeaton Friary Co. Limerick, where Blessed Patrick O’Hely and Blessed Cornelius O’Rourke are buried. The friary was destroyed and reoccupied several times, before being finally abandoned in the 18th century. (Open source).

O’Hely and O’Rourke were left hanging for 14 days. The English troops lowered their bodies close to the ground so wolves and other beasts would devour them. The two martyrs were left untouched by the animals. When the Earl of Desmond had learned of what had happened, partly to try to make amends for the mistake of his wife, he used what little authority he had left to have the ,arturs cut down. They were brought to Clonmel Co. Tipperary where they were buried with great honour. Later their bodies were moved to the Franciscan Friary in Askeaton Co. Limerick. In 1992, Pope Saint John Paul II beatified both Blessed Patrick O’Hely and Blessed Cornelius O’Rourke.

Reading about these martyrdoms puts one in mind of the martyrs of today. It reminds us specifically of priests and religious who struggle during times of persecution to continue their pastoral work and administer the Sacraments to the faithful. One example that springs to mind is that of Fr. Hovsep Bedoyan in Syria. Fr. Bedoyan was an Armenian Catholic priest based in the Syrian city of Qamishli close to the Turkish border. In November 2019 he was traveling with his father and an Armenian deacon to Deir Al-Zor in eastern Syria. The area had recently been freed from ISIS and Fr. Bedoyan was traveling to the area to re-establish an Armenian Catholic parish that had previously operated there. On the way to the church, an ISIS gunman opened fired into the car the Christians were traveling in and killed Fr. Bedoyan and his father. The deacon traveling with them was wounded. This is just one of many examples from Syria, and from around the world, of clergy being martyred during their attempts to minister to God’s People.

Fr. Hovsep Bedoyan. An Armenian Catholic priest in Syrian, killed by Islamists in November 2019. (Credit: Aid to the Church in Need).

The similarity between the killings of Fr. Bedoyan and the two Irish martyrs are striking. Both were traveling on a mission of peace to preach the Gospels and administer the Sacraments. When traveling to the area of their mission they were martyred. The persecutors were very different in each case, but the results were still the same. As followers of Our Lord Jesus Christ we stand with the martyrs of yesterday, today and tomorrow. For this reason, it is important that we in Ireland continue to pray that through the intercession of Our Lady and the Irish martyrs that Our Lord may give the comfort and strength needed by the persecuted Christians and martyrs of today. And that they may continue in the Faith and carry out the Church’s mission to all nations and people, as the Church is commanded by Christ to do.

The exact date in August is disputed. The most common date is the 31st Augusts, the next common is the 22nd. All sources agree the martyrdoms took place in the second half of August.

O’Hely and O’Rourke’s martyrdom has been dated to 1577, 1578 and 1579. The date of 1579 is unlikely as the Second Desmond Rebellion is not mentioned in any of the accounts of the martyrdom. O’Hely was consecrated bishop in 1576. On his way to Ireland he stopped awhile in Paris to study and lecture, it is therefore unlikely he would have reached Ireland in 1577. For these reasons 1578 is the most likely year the martyrdoms took place in.